We were told to stay clear of the well. Most of the time, we did. No one knew why, and no one cared. Down Innsmote Road, the long abandoned row of crumbling houses on the way to school, it lay beneath the shade of a droopy branched willow, in front of the old Leibowitz house. The house itself had fallen down years ago. The expansive section was now consumed in thick weeds and wild flowers, but we seldom played there. We didn’t like being amongst the derelict homes and the decaying foundations, and I would run past the well whenever I had to pass it alone. The footpath sloped dangerously close to the wells bare opening, itself hidden in long grass. Where the light touched the top most part of the gaping pit, it’s mossy brick inner surface was just visible. Below that, there was only darkness.

Me and Henry walked down Innsmote Road every day after school. Our friendship was an unlikely one. Henry came from a poor town down south. His family name was neither prominent nor wealthy, and it was new in a very old city. Raised as an only child by his mother, Henry had not had a fair life for such a nice kid. Of course I had no idea at the time, I was only young, but his father had been a mad alcoholic. His mother had left town for Henry’s sake. He never spoke of this, as he was probably too small to remember it, but we never mentioned his father regardless. It was clear he did not wish to remember him. Henry was not a particularly bright student, either. The day we met was the very first day of school, when he leaned across from his desk to mine and asked if he could copy my answers. The test was for math, hardly my strongest subject, but I beat him up for it anyway, after school. He nearly past out from the sun alone. I felt bad about beating him as I’d done it. He was a short, skinny kid and he couldn’t put up much of a fight. I bought him an ice cream that day, and we talked properly for the first time. Afterwards we became inseparable. Even though I played football on hot days and he stayed in the library and read, even though he copied my answers in every test, we were best friends.

In the bitter wind and the stinging rainfall, we did not laugh or share the days experiences with each other as usual. We endured the storm together, in silence. We would usually go down Church Street to the arcade in town, but today it was pouring with rain. The storm was one of the worst I have ever seen. The gutters were overflowing like flooded rivers and the bare foundations of the Innsmote houses creaked and groaned in the wind. Surrounded by the constant moaning of the old homes and bombarded by the screeching wind and ice cold rain, we were only more determined to get out and get home. I lived further than Henry, on Mayrary Ave, and I walked hastily, dripping wet. We walked straight ahead, until we reached the well. The slope was more evident than ever today, rainwater rolling down and draining into the hidden pit below. Were anyone other than us to walk past at that point in time, they would have not even have noticed the well mouth, wide open and hungry. We turned to look in it’s direction, an unspoken acknowledgement of our fears that we performed daily. It was then that Henry fell. He had misplaced a single step, and collapsed with a painful, muffled cry onto the concrete. Blood from his nose mixed in with the rain and slowly disappeared. As he tried to get up, pushing his body up on one arm and outstretching the other, he slipped. His yells echoed down the empty road. He slid down too fast for me catch his hand. His chin hit the concrete, and he let out a pained yelp. The skin had been ripped deep. I called his name, and ran towards him. The wind struck me hard, and I toppled down. I rolled across the slope, registering a sharp sudden pain in my side, and fell in the swamped weeds, mud soaked through to my skin.

“Henry!”, I cried, reaching my arm out blind.

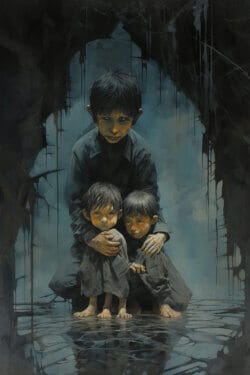

A sob of terror came from up ahead. I forced my eyes open and saw Henry, no more than a foot from where I lay, hanging desperately onto the well opening. His chin dripped blood. His slippery fingers were only barely keeping hold of the mud covered brick.

“Henry!”, I called again, willing myself to get up.

As soon as I began to pull myself out of the weeds the pain in my side burned and sent spasms of pain shaking through my bones. I collapse, in pain, and tried to call his name again. I wanted to get up. I tried again, this time with his screams to guide me as a hand slipped. Once more the pain, the unbearable pain sent me into the dirt, so close to his little fingers.

“Help me!” he screamed over the rain, “Please help me!”

I lifted my head feebly to see Henry’s eyes fill with tears. With one last sob of fear, his hand slipped. In an instant he vanished into the well. In that moment, it all went silent. Sound was gone the moment I saw the top his little brown head slip out of view. I heard only the thumping noises, dull hard sounds from far away, and I realized that all I could hear was my best friend hitting the brick well walls as he fell. Ignoring the pain, ignoring the storm, I lifted myself out of the dirt and ran. I didn’t stop until I reached Mayrary Ave.

I got home to find my mother waiting on the steps, her face wide eyed and her mouth curled into a scowl.

“Where have you been? Get in here.” she hissed.

Her words were insonorous and drawn out. I stumbled indoors, leaving wet footprints on the carpet. She slammed the door shut and yelled. She went on and on. I hardly registered a thing she was saying. She screeched about the weather, how worried she’d been. How I could have gotten hurt. I started to cry. At first I could only manage weak sobs, but I eventually found myself curled around my mothers legs, weeping. Her anger was replaced by surprise. Guilt perhaps. She asked what was wrong, why was I crying? I only bawled more, knowing I could never tell her I was ashamed. Ashamed I let my best friend die.

The search for Henry was longer and more painful than I ever imagined it could be. His mother rang us first. I told her I hadn’t seen Henry after school that day. I told her I didn’t know where he was. What I didn’t tell her was that I watched on as Henry fell to his death. What I didn’t tell her was that I killed her son. After three weeks Henry’s photograph was in newspapers. We saw his mother on the television often. She was crying. It was a local disappearance, and it garnered only local attention. The police spoke to me. Children at school spoke to me. Teachers spoke to me. I told them the same lie I had told Henry’s mother. Each time I knew I could never go back. The consequence became worse every time I hid the truth. Eventually I knew I could never tell anyone what had really happened that day. Sometimes I liked to believe it myself, that I had not, for once, walked with Henry that day. That I too was mourning his disappearance, and not his death. The well was never even checked, because I said I had not walked with him that day. A teacher claimed to have seen him walking in the direction of Chruch Street, and it was presumed he had gone to the arcade. Murder was suspected. Chruch Street corner was where we met, everyday. After that I took the Chruch Road route. It was much longer.

By the time I was thirteen no one spoke of Henry anymore. The police search ended indefinitely after a year, having found no evidence. Until any emerged, they could do nothing but wait. Henry’s mother left town a year later. As I grew up I came to disbelieve that I had ever known a Henry at all. I told myself that I had been walking home alone the day that Henry boy, the quiet one I never talked to, disappeared. I wondered if they’d ever find him.

By my last year of high school I had made new friends. Mostly footballers, like me. Times changed quickly. We went from playing at the arcade to getting drunk so soon. Girls and cars were more important to me now than cheating on maths tests and buying ice creams.

One day, as I was walking home, I found myself enduring the worst storm our town had seen in eleven years. We had to cancel our after school match. I was devastated. As I heaved through the immense force of the wind and the piercing rain it occurred to me that the Church street was a needlessly long walk home. In weather like this, I was surely better off taking the Innsmote Road. The road was lined with decaying houses. I passed caved in roof’s and overgrown rubble, all the while trying to force myself through the ice cold storm. It was as I walked past the crumbling area of pavement that a shiver crawled through my skin, and I turned to see a black pit in the earth, half hidden in the grass. How I had even noticed it, shadowed as it was beneath an overhanging williow branch was beyond me. I slowly turned to continue walking against the storm, just in time to see a length of corrugated iron come howling through the air. I was paralyzed in shock when it struck me, throwing me back and sending the taste of blood rushing into my mouth. I felt myself hit something hard, then light rapidly spiraling away from me. Cold air swept past my face, and the blood rushed to my head as I descended ever further, the light growing ever dimmer in the distance.

When I came to I was in pain. After a pitiful attempt to stand up, I realized I had landed on my leg. Feeling around in the dark, I came across the split bone protruding from my knee, and something wet on my fingers, I screamed, and my cries echo a thousand times, all the way up the well until they faded away outside. With much effort I made myself look up. The speck of light above me was like a distant star. It took me sometime to realize that I was partially submerged. The coldness of the water was only as awful as the smell down there. Underneath me there was water and mud. All around I was surrounded by blackened brick walls. The constant noise of water dripping made me breath heavy. In my distressed state of mind I though I hear someone say my name.

“Who’s there?” I yelled, looking around madly into the empty blackness.

No response. I shivered in the cold, staring aimlessly into the darkness. Next to me, someone mumbled something I couldn’t make out.

“Who are you?” I screamed, curling myself up close to the wall of the pit.

Someone mumbled louder. A raspy noise. I knew I had heard it. A cold tingle rain down my neck as I made out an unclear shadow against the wall beside me. My heartbeat was electric. The thing on the wall began to shuffle towards me, mumbling again louder. I wanted to scramble away, to feel safe in the light. But I couldn’t. I was trapped. I was trapped with someone else. The mumbling thing that inched closer and closer. I could feel it’s breath now, on my face. Tears streaked down my face. I opened my mouth to scream, but no sound emerged. Slowly, I turned to look.

In the dark I could not make out the face precisely, but I saw all I needed. I screamed in horror at the sunken eye sockets, the gaping jaws and the dripping, rotten flesh hanging off what was once, surely, a human face. It’s slender hands burst from the water and wrapped around me. It hunched over me, and I finally understood what it was saying when it hissed in my ear:

“I’ve been waiting for you…”

So: your friend falls down an old well while its been raining hard, and instead of thinking that he might need help, you would just bolt? I wonder what the chances are that Henry eventually drowned or starved to death down there. Very unsympathetic main character. :/

it was predictable but apart from that i really loved it 7.5 out of 10

Please add on…it was so good

Kind of predictable but I loved either way! Great Pasta and I can’t wait to read more!

It was a bit predictable, HOWEVER, the suspense/build up was fantastic! Overall, an 8.5 out of 10. Keep writing, love 🙂

It was quite predictable, but you built it up well and there was tension throughout. Despite me knowing what was going to happen, you kept me enthralled and interested. 4/5

Not that great really, it was obvious where it was going. It also needs editing as there are several mistakes.

Was a little predictable, the build up was great. However, the only reason it gave to stay away from the well was the danger of falling in it. Which doesn’t seem very major, because there’s a lot of mystery surrounding it.