They kept sending us money, that was the problem.

Even after the drugs which made your mind spiral into rainbow hell, and the noxious smelling salts, and the obscure rituals, they never cut funding.

Even when we got desperate, they still kept pumping in the surplus of our good taxpayers. It wasn’t just money either, they kept us in good stock of all sorts. This included the drugs, obviously, alongside the sleek and sinister machines, chrome-plated man-made horrors.

They kept us in good stock of all sorts of horrible things, yes, but arguably the worst things they kept sending us were the kids. More hypersensitive and/or strange children from all over the country than you can shake a menacing middle-school bully at.

During my career, we’ve only actively lost four of them due to our experiments. We were never told what happened after they were released from captivity, back into the wild. I sometimes think about how many killed themselves, how many became vegetables from our psychological meddling, how many died from something we’d given them, the effect delayed or slowly accumulating. I even wonder how many died from something unrelated, a car crash or something. I think, even if that were the case, it would still be our fault somehow. When I ponder this at night, I am reminded why I must not have children. I could never deserve such a thing after everything I’ve aided in doing.

One of the ones who died, Thomas Landitt, did so in my arms. It wasn’t even anything to do with our studies, really, nothing unusual. He had very extreme asthma, along with a knack for talking to ‘devils’ in his sleep, and the smoke we made him inhale had triggered it. I tried to help him, I prayed for him there in that blank-walled, nameless room, but when I recognised that there was likely little hope for him, I simply resolved to embrace him, telling him how sorry I was, praying to him instead, for forgiveness. The medics came just as Thomas Landitt had finally given up on taking his last breath.

They never stopped sending us money, no. But eventually, after one too many Thomas Landitts, they stopped sending us kids.

One of the guys we had working with us, a veiny-headed science freak who was deemed too smart to live among normal people, had come up with a theory doubtless born of sleepless nights and morbid over-thinking.

It was based around the concept of a controlled reality, an artificial life under the control of an overseer, a simulation. His theory went that if a person was raised from birth in an environment where he came to know everything as completely predictable, that he would become so used to understanding what was next that even if everything no longer controlled, he would still be able to do so. So apt and guessing what was supposed to come next that he could do it even when his life was not under complete control.

A home-grown clairvoyant. If they would not give us unusual children, we would grow our own.

It was an idea so utterly stupid and outlandish that it obviously had to work. Anyway, What else were we going to spend all that shiny new government cash on?

Over the course of the next two years, we got to work building a small town. As our ‘Simulation Kids’ would come to know it, the town was in the heart of Illinois, and had been there for around 150 years. In reality, however the town was brand-spanking new, with the buildings all touched up to look old and wizened, located in rural Montana.

We had drafted in around 500 people to act as townsfolk, some of our own agents as well as unsuspecting US citizens and their families who had been lured in by the promise of a lifetime of free healthcare. There were a few large families fresh from over the border, who would have been willing to sacrifice their firstborn son to the one eyed pyramid if they never had to go back to Mexico.

One of the guys who worked in the IT Department, Ron, a surly little bug-eyed introvert who as far as anyone knew spent months down in the tech office, practically fell onto his face and broke his spectacles trying to get put in the program. Ron had suffered from what had been diagnosed as pretty severe autism all his life, and the chance to do what he had struggled repressing for a living sounded like a godsend to him.

All were briefed that they were to follow a strict routine every day, and also trained them in what to do if anything ever went wrong. Everyone had a method of contacting security, government agents temporarily demoted to small-town cops, and knew what they were to do if the system ever cracked at all. Cover it up and smile.

The routines tightly constricted every single moment of their day, every day of the week, apart from in the evening, when they could do whatever they wanted in their houses. The centrepiece of our performance was ‘the morning scene’, where each person would leave their homes at the same time and go the exact same direction. It was decided that they must follow their routine every moment of the day, so that the lives of the Simulation Kids could be completely reliable.

Ron used to damn near explode whenever he thought that the other residents weren’t doing ‘well enough’. Once, when his neighbour hadn’t woken up early enough for a dress rehearsal, he berated him thoroughly across his front lawn fence. Another time, after requests from the exhausted populace for at least a week off early in the process, Ron, who had vehemently protested against this, was found weeping to himself under his bed. There were a lot of complaints, indeed. Some of the residents compared it to torture, and many of the less thick-skinned had begged to be excused.

The whining wasn’t only due to the gruelling nature of their job, however. Many complained about the location of the town itself. Some heard strange noises in the night, spotted the animals acting unusually, and even said they thought that the trees were somehow menacing. The other thing was the dreams. Women would hear children crying or have gutting dreams about their own children which they couldn’t bear to describe, while men had dreams of burning towns and cities. Two different men told us about essentially the same dream, where a naked woman was impaled from a meat hook in a dark room, not a scar or any sign of injury on her. However, she held a small, baby-like form against her chest, which was dripping with blood. The children, meanwhile, had pleasant dreams of talking animals and flying.

For us, and for what we planned to do in this area, this seemed like just about the perfect working environment.

After about three years of this rehearsal phase, the complaints almost ceased to exist. They became like a real community, the residents claiming they were starting to actually enjoy their routines, along with the promise that it would likely only be a few more years before they were allowed to go back. Personally, I only ever visited, and stayed in the obscure headquarters ten minutes from the town over the course of those twelve years, but whenever I visited in that third year of the residents settlement period, the environment of the town usually struck me as unnerving.

It was like a cult commune, everyone strolling around with the over-exaggerated zeal of Disneyland employees, all swapping positive sentiments with each other on the street. The way they said these things was prayer-like, a rictus repeated so regularly that it had lost most of its actual meaning to them, but at the same time something that they had been so thoroughly ensured to believe with all of their being that they dare not forget it.

And they were all so tired. They hid it best they could, of course, but you saw that it was starting to wear on them properly, even early on. When they’d finally adapted to it, it was even worse. It was sad, watching all of them groggily doing their best to look like they were well-functioning people.

I told the director, Josh Bleeker, about how strange I felt whenever I went into the town. He agreed, but he said, in a firmer voice than usual “we’ve got one foot in this mess already Kate, three years worth of foot, in fact. All we can do now is shove the other one in and pray.”

Josh was the third director of our organisation that I’d served under during my time, and not the last, but he was, at the time, my favorite. Josh was a relatively normal man. Obviously probably not by a lot of other people’s standards due to the nature of our job, but he was never weird or creepy when he came in. He had a very encouraging nature, a sort of warm presence which almost gave you the will to keep going.

He had a catchphrase that he’d usually crack out at team meetings, and occasionally in conversation. “The show must go on!” He’d say, grinning. It was also a bit of an inside joke too, about how the State were practically shoving us along with all the resources we were given. It worked quite effectively in a variety of contexts. He said it with his full chest, bellowing out to everyone to get us riled up. He’d say it in private, encouraging one of his workers if they expressed concerns. He’d say it grimly, seemingly half to himself, when something awful happened. And while this last example didn’t directly support us that much, it showed us, in my mind, that he wanted to let us know that even he was tired of this stuff.

I was in love with him to quite an unhealthy extent. Either because he was actually just very charismatic, or because I lived with him for more than a decade, like Stockholm Syndrome, but between prisoners. The fact that he was also one of the only among my male co-workers who I was confident wouldn’t be a serial killer if things had turned out differently for them probably also helped.

Admittedly, the other women weren’t much better, myself included. The fact that he had to deal with all of our imperfections and lapses in sanity, and still treated us like people was one of the things I used to justify my infatuation for him the most.

During our rehearsals, he was like a movie director, rushing around and giving everyone in the town notes. He even got them saying his catchphrase. While I had to have every trace of it scoured from the internet, I had a video on my phone of all the kids in the town, all lined up, smiling, with Josh at the front. All of them say “The show must go on!” And laugh.

After that, Josh came up to me to look at the video. When I remember the way he looked at me then, I wonder if he really did like me back, and I curse myself for not doing anything about it.

He’d play the role of the unseen mayor of the town, appearing only at festivals, and, after some discussion, the town was named after him, Bleekerville.

So, after roughly 5 years of building, training and putting our little, fake town together, we finally decided it was just about good enough. It was finally time to shove the other foot in.

We’d decided that three children, each raised in different households, would be the optimum for this first test of the process. Three families were randomly selected to bear and raise the kids, none having a say in the matter.

One woman, Abigail Meline, was distraught at the news. Her and her husband had never wanted children, and admitted that she personally hated them. She still had no choice. It was barbaric, doing that to her, I knew that at the time, but I also knew, or I thought, that it was fair. It served a purpose, one that this time, was going to work for us.

A sign of things to come, all three children were conceived on the same day and were also born on the same day. This was not our doing. To us, this unexplainable event served as some kind of proof that we were heading in the right direction. Despite this, I could not shake off the feeling that this coincidence was not a miracle or a success, but a warning.

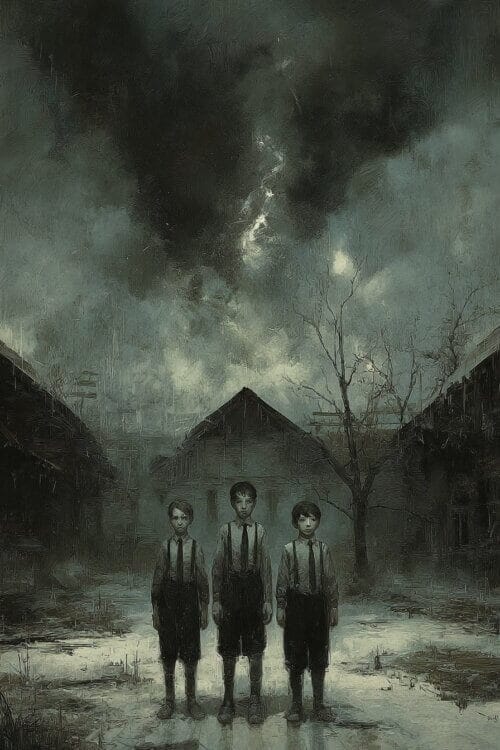

They were creepy little shits, that was clear as soon as they came out. Gangly with knobbly bones visible from their stretched-out looking skin, and sunken eyes. Each, despite one being from a Mexican family, one from a Polish Jewish couple, and the last a white-as-wool ginger, had similar hair, lanky and straw-like. Lifeless. Initially, we thought they’d somehow all be born with the same genetic deformity, however the results of the tests we took on them suggested we simply had three healthy baby boys.

Dennis was the Melines’ boy, from Abigail and her husband James. His head looked like it was squashed out backwards, a sort of bulbous feature at the end. His voice was an excruciatingly high pitch, even for a child, and when he laughed spit flew from his mouth like an unavoidable torrent of bullets. A very sensitive boy, he used to start screaming and covering his ears whenever he heard a somewhat loud noise, like a car going by too fast or something being dropped. Abigail tried her best with him, she really did, she always had to reassure him whenever anything happened, which ultimately exhausted her.

Louis was the biggest of the three, raised in a Mexican family who already had three other children. He ate a lot, more than you’d expect any child who was as bony-looking as him to eat. Instead of growing outward, he continually grew upward at a rate too fast for even a young child, getting pains from this which left him occasionally bed ridden, as well as gangly and 5’1” at five years old. He rarely went to sleep as well, Mr and Mrs Cabral would sometimes wake up in the middle of the night and hear his bunny-rabbit teeth clacking and his pale lips smacking as he demolished the consumable contents of their shelves.

Finally, there was Eric. A scrawny ginger kid, smallest of all three, Eric was, without a doubt, the most evil-looking child you’d ever see. His cheeks and eye sockets were even more sunken than that of his ‘brothers’, and while the Trio’s similar ugliness made the other two look like gormless zombies, it made Eric look like a cunning, bloodthirsty vampire. His behaviour made this even more believable, he would sneak out of bed and sit up on some ledge somewhere all night, jumping out at his groggy family members, scaring them shitless. He used to take small bugs and slowly dissect them with hairpins, then throw the remains in the toilet, say a prayer and flush them down, thanking them for their contribution to ‘science’, even occasionally weeping for them. He was a nuisance in general, always going around Bleekerville and knocking over post-boxes, or throwing leaves over driveways. Once while someone was up a ladder as part of their weekend routine, Eric tipped the poor man back down onto the floor then ran off.

His dad, in particular, hated him. Mr O’Leary had been raised in a very strict household, and his new son enraged him with his insolence. He would berate him to the point that we were worried he would resort to physical punishment for his son.

At school, the trio immediately flocked together on their first day, not a single word between them. That’s how most of their ‘friendship’, or more companionship, seemed to operate, in complete silence. The only one who usually spoke was Eric, and that was to give orders. They became like his henchmen, Louis seeming happy to do whatever Eric wanted for the fun of it, while Dennis occasionally complained, but was swiftly intimidated into shutting up and getting on with it. They rarely interacted with any of the other kids at school, only getting into fights with them. They weren’t bullied, that had been trained out of the normal kids, who had been moulded into model schoolchildren, eager to learn and follow rules. If anything, the trio were bullies, harassing other children and stealing their belongings. One little boy said that he didn’t like them, saying that the way they moved reminded him of spiders.

They grew up like this, abnormal children who took a sadistic pleasure in causing disruption, living in a reality that was trying its hardest to be as flawless as possible. On the experiment itself, sacrifices of those who lived in the monotonous purgatory of Bleekerville were not in vain, as we had seen quite a fair amount of success from our test on the three. We’d had weekly “doctor’s appointments” with the kids where they were tested. It was all pretty old-school stuff (‘Artichoke Tests’ as we sometimes called them), but it had worked. All had been able to seemingly see things beyond curtains and even walls once we had them on drugs.

One day, we were attempting to see if any were capable of something we’d rarely been brave enough to test. There were a bunch of us, Josh included, packed into a dark little room and watching Louis through a one-sided tinted glass window. The giant of a boy was sitting at a table, a small glass of water sitting before him. He was clenching his teeth, hard as he could, with the veins standing out on his forehead and neck. From between his teeth, saliva dripped rapidly, and he was starting to twitch a bit.

In front of him the glass of water was sitting definitely, only a few inches from his head, which was nearly resting on the table as he keeled over from effort.

For a moment, he was sent back to his seat, panting and sweating. Then, regaining his second wind suddenly, Louis sat bolt upright, his eyes steely, and the glass toppled over.

The grim viewing chamber turned into a bellowing football stadium for a while after that, our cheers were so loud that Louis heard them from behind the reinforced walls and we had to be silent while he was herded off, back to the town. We had a sort of party at the small headquarters outside of town that night, pretty tame by most people’s standards, I’d expect, but we had to celebrate somehow. We’d had much greater results in the past, but never had we spent so long working towards them. The little science freak who thought of the whole simulation kid idea was getting pats on the back all round, and he looked like he hadn’t gotten this level of praise since his last spelling bee.

It was a good night, for everyone else at least. Especially this snake from another department, Lisa, who managed to slither her way to Josh’s ear. He was hanging around her all night, smiling at her while she talked, slowly hypnotising him. I only spoke to people so as to not look like I was just glowering at her the whole time. I don’t like to be jealous, but still to this day I cannot understand what part of him was at all entranced by her.

After he had finished his obligatory rousing speech, Josh, ever ending interactions with his team with a little bit of lightness or relatability, motioned over to Lisa.

“Now, I’ve got something else planned for this evening, folks, if you’ll be so kind as to excuse me?” He winked, turning away for a moment then quickly turning back again, slightly tipsy. He raised his arms, hands curled up into victorious fists above him, belting out; “THE SHOW MUST GO ON!”

Everyone laughed, everyone clapped. What a guy. What a guy. Trevor, one of our security guards who was by my analysis likely a psychopath whooped and called; “Go get ‘er J!” after him. Lisa smiled at everyone, her red lips pursing into a smug expression. Her eyes lingered on me. She knows, the fucking cow! I thought, biting down on my lip to keep in the tears.

I went to my room not too long after that. There were no other reasons to stay at the party, especially when Trevor started desperately and somewhat half-heartedly hitting on me. All I wanted to do was cry all night. It had become too much for me. I hated those children, and despite our recent victory, I had no enthusiasm nor hope for continuing our project. I couldn’t stop thinking about all those people in Bleekerville, living like pieces of code, only able to perform one function, while we basked in hedonism in our little alcove, getting irritated that the little disabled children we were experimenting on weren’t exploding heads with their brains or stealing the thoughts of world leaders. But when I tried to cry, it was like I’d sucked them all back up at the party, trying to hold them in.

Instead, I just decided to go to sleep, hoping to see Josh. If I couldn’t have him in the waking world, maybe I would be allowed to see him in my sleep.

I did not have pleasant dreams that night. Nobody in the whole of Bleekerville did, for that matter. And when they awoke, life became its own slow nightmare.

Everyone had horrible dreams that night, myself included. While I slept I was given a vision of some kind of mass grave, dozens of foetuses, swamped in blood and gore, all lying at the bottom of some great pit, while a woman quietly wept in the background, a cry of regret and sadness.

In addition, when we awoke, each of the Trio’s parents called us up, all at roughly the same time, telling us of the swelled, red marks they had found on their children. Upon inspection, each had the exact same wound, which looked as if it had been wrought with a cracking belt, in the exact same place.

We made the connection, after a few hours of dumbfoundedness, that this was proof of some kind of deeper connection between the boys, deeper than their strange bond, or even their synchronised births. It was a connection of flesh and mind, one which bound the lives of these three terrible creatures together. One of them had been beaten, which had somehow had the effect of wounding all three.

Our problem now was finding and sorting out which of the parents had done such a thing. Of course, we were immediately suspicious of Mr O’Leary. The fits of rage he burst into, especially towards his son, did not indicate a man who practiced control. Even the way which he treated others was akin to the behaviour of an abuser, if a restrained one, due to his current environment.

“Just because I have a good, disciplined way of dealing with my son after he misbehaves doesn’t mean I’m beating him!” He said when me and another of our organization came round to his house. “Who raised you people? That’s what I’d like to know. No, you folks really need to get your values in check!”

We were in the living room, identical to every other living room in Bleekerville, a calming and idyllic room with a somewhat retro decor. Identical apart from the shoddily plastered-over crack in the wall near the television, which O’Leary had struck after the New England Patriots lost a match.

I hesitantly attempted to calm him, which was like approaching a raging bull. “We’ve inquired about all the parents of the subjects so far, sir, this is simply-”

I was suddenly cut off as O’Leary bolted out of the room, chasing after Eric, who had been peeking around the doorway, silently observing us with massive eyes.

“Come back here boy, dammit! I want to speak with you!”

After another half an hour of O’Leary coaxing his son into claiming that his father would never lay a finger on him, we left the house. The little runt had a small smirk on his face as he spoke. It was sort of smug, as if he’d gotten away with something really bad.

The other two homes didn’t lead us anywhere new in our investigation. The Cabrals had made their case quite convincingly, and we didn’t really suspect the small, tired little man and woman of doing anything to their son, who despite everything they clearly showed affection for. I only got a small glimpse of Louis while we were in the house, but the way he looked at his siblings, who were all a bit shorter than him, resembled the way the average child might look at sugary treats in the window of a candy store. Out of reach for now, but still extremely tempting.

Abigail was breaking down when we spoke to her. She too, apparently, had been struck with the horrific dreams, so bad that she could not even speak about them. I felt so bad for her that I comforted her for a long while, almost forgetting to question her.

When we got back to the headquarters, we received even more awful news. There had been a suicide, someone from Bleekerville, finally cracking under the pressure, had jumped out in front of a car. The man who drove the car, having gone at the exact same speed in the exact same direction every day for the past decade, simply continued, running the guy down, and then driving off.

As it turned out, it had been Ron from the IT department. The same once-troubled man who had jumped at the opportunity to be involved in what he saw as a rigidly controlled paradise. His neighbors had heard him screaming from next door in the early hours of the morning, after awakening from horrors of their own, and he had stumbled out onto his lawn at around 6 AM, ranting about how he’d made a terrible mistake.

His neighbor, trying to calm him down, had asked what the mistake he’d made was. In response, Ron had apparently scrambled over to him, upper body leaning almost horizontally over the white fence with his nose almost pressed against the neighbor’s face. He had then said “we’ve all made a mistake man, all of us. It’s my fault more than yours, I know, but you’re all still going to get punished for it. Everyone is. Except for the children, that’s what it wants to protect. The real children, I mean. We’ve gone against what’s right. And you’re all gonna get punished for it.” Seeing the car moving down the road at that point, Ron had turned back to his neighbor, grinning.

“But not me.” And then he ran off, standing in the road with his eyes closed for five whole seconds before the car hit him.

There had never been any real injuries in Bleekerville, so the skills of the doctors at the mostly calm town hospital had slowly deteriorated. Ron was dead two hours later.

“We’ve lost an integral part of the project today.” Josh said at the following meeting. “While he wasn’t a social animal, Josh was a shining example of…of perseverance, and I’m sure that he’d want us to keep going.”

But what Ron had said before taking his own life could be simply dismissed. It was obvious what he had meant when he said that we were going against nature, but who was punishing us, and why were the townsfolk not exempt to this punishment?

Before we could investigate any of this further, more disasters struck. It was like something had been lying in wake that whole time, up until Louis had finally tipped the cup over. The tipping point. Then, when it sensed we finally felt genuine hope for our little blasphemous project, it had decided to finally emerge, watching as everything leisurely rolled downhill for us.

The attacks of the animals came next, like the plagues God had sent to Egypt in the bible. Ambiguously nasty-looking insects attacked the townspeople, and rats were found stashed inside dark places in the houses. All were rabid, attacking people and devouring their food. There were wild dogs too, galloping into the town in packs, who would snap and bite adults, but sit and allow the children to stroke and even ride them. Meanwhile, whenever any of our Simulation Kids neared these animals, they would freeze in what seemed to be shock, or fear, for a few seconds, before turning tail and scampering away.

We all agreed that these events were not a simple coincidence. The dreams, Ron’s suicide, the animals. It all had a sort of common theme; the children. The normal children were safe, their dreams pleasant and no harm coming to them, while the Trio, our children, were feared, an element of the unknown which frightened whatever we were dealing with.

Being the sort that we were, it was obvious to us that this was some kind of spirit. Researching the beliefs of the Natives who had lived in this area, we discovered the tribe that lived on the land had worshipped a wide variety of gods, who were more spirits that symbolised and stood for specific elements of life or nature, not quite personifications, but more guardians of these aspects.

One which stood out for us was the Warrior Mother, an entity who represented what the Natives observed as the fierce, protective nature of women for their children. There were several legends of this spirit appearing as a savage 10-foot tall giantess and killing members of rival tribes who had killed children. In other tales, one recorded in the diary of a Christian missionary, natives said that the crows who ripped apart another of his congregation were sent by her to avenge the young children he had been sexually abusing during their visit.

The connections were harrowing, and at this point it had been brought up in team discussions that it might be a good idea to abandon the project. Had we really achieved that much in the time we’d been here? Was it really worth endangering and torturing these people for god knew how much longer?

“No, no, I don’t want any of that, alright?” Josh, by this time, looked like a madman. He’d been deteriorating since that party, as if that bitch he’d chosen to go with had somehow sucked out his soul. “The show must go on.”

It was getting irritating at this point, it did nothing more than dampen everyone’s mood and certainly did not work wonders on our morale as it once had.

In the end we decided to communicate with our enemy. We had a guy for this sort of thing, a real eccentric everyone called Mister Zap. He was tall, with dark skin, and a soft, soothing British accent. He set up in the basement of our headquarters, where he said he could ‘feel the currents the strongest’ (an odd gentleman, as I’ve mentioned), took some speed, and meditated, drifting off to sleep with a quaint smile on his face. All of us watched, yet again holding our breath in anticipation for something we only dared to truly believe in.

Afterwards, his eyes snapped open, and he began to purposefully stride around the chalk circle he had drawn for himself.

“One of these.” He said, curtly. His voice was a lighter pitch than it usually was, but at the same time more assertive. “Be quick, I dislike these arrangements. You are the ones with the odd children and the fake settlement, correct3?”

“Yes. We’d like to ask why you’ve been attacking us?”

“Because you are an affront to all I am meant to represent. I know what you have done to children previously. All children of the world are mine. All of them. And while my reach does not expand to beyond this place, I will not allow you to victimise them here.”

“None of the children here have been-”

“You have caused turmoil to the children who were brought here, none have had enough sleep and all are tired from having to do the same thing every day.”

“We’re doing a job here…er, ma’am.”

He snorted harshly. “Do not address me as anything of your modern world. The matron spirit need not be a woman nor a man.” His face then twisted into a frown, eyebrows packing in together darkly. “I dislike the treatment of children in your settlement, yes…but naught affronts me more than your…activities on my land.”

“The children?”

“Yes. You aim to create your own shamans I gather? For the service of your rulers? They disturb me. All children in the world, all children of all nations, they are mine, as I have said.” He shivered. “But those things are not mine. And they are certainly not yours. I will not allow them to live here any longer.”

“Well, should we move them then?”

“No.” He smiled without humour, raising his chin authoritatively. “You will kill all three of them. If you have not done this in three days, or if you try to move them elsewhere, a great storm will sweep through this place and take with it all you have built, killing every man and woman foreign in blood to this land. This is my final ultimatum.”

Mister Zap returned, and the spirit was gone.

Over the next few days, it was broadcast on TV that there were sudden and unexplained signs that sometime soon, a devastating storm would sweep through our area. The winds were high, so powerful that mailboxes got sent flying from the ground, and people were told to stay inside. The animals continued their erratic behaviour, squirrels jumping down onto people from trees and birds flying headfirst into and splatting all over windows.

Among all the chaos, we had lost four citizens of Bleekerville on the first day after our ritual, all of them children and amongst them our three subjects. The group had gone missing suddenly, sneaking out of the house at night, while the other had gone missing early in the morning on his way to school.

We had the whole town on the manhunt in the surrounding area, which, due to the current nature of the animals and the weather, was extremely treacherous. Eventually, they found the Three, who had been sleeping in a small den in a bit of wood where no animals lived. They had the other kid with them, who had apparently been forced to do all sorts of unpleasant things for them, including seeing how long he could hold his breath for, how many times he’d have to head butt something for before he went unconscious, and what they were even planning on surveying before they were found was how long the poor kid could go without sleep. He looked battered when he was recovered, and taken back to his home. When we asked why he’d agreed to do all this, he told them that he hadn’t, not initially.

He said that when he refused their demands, the Trio would close their eyes, and give him ‘Nightmares’. This, at least, was a sign that they were developing as we wanted, but not in a way which we could control.

We didn’t know what to do about them. After this incident, we’d placed them firmly under our surveillance in the headquarters, telling everyone in the town to get back home. All three looked somewhat bashful, but by no means guilty. Eric, as usual, looked quite pleased with himself, and even proudly showed us his notebook in which he had been recording all of their prisoner’s ‘statistics’. The team stayed in the briefing room for almost 5 hours, arguing back and forth over what had to be done.

During most of this time, Josh sat with his head in his hands, hair tousled up and eyes rimmed with red. There was something beyond natural disturbance going on with him, and everyone knew it. He’d take to pacing around when it got quiet, muttering the same five words himself. “The show must go on.” It was around then that I could never imagine being so rallied and emboldened by such a cheesy, clunky phrase. He had lost all of his charisma. He only spoke once, and, uncharacteristically, it was to suggest the course of action that the spirit had demanded.

The sun went down on the second day since we spoke with the spirit, and the winds only blew stronger. In the night, Eric had asked to go to the toilet every hour, and had clogged up the toilet with so much toilet paper that the plumbers were still cleaning them out by mid-day.

That day was grim. Everybody knew what had to happen. Everybody knew the decision we were going to have to make, but nobody wanted to. It was deathly silent in all of our offices, and every glance at the clock made our stomachs churn.

I decided that morning that I was going to quit. I had had enough, I was no longer passionate about what we were trying to do, I never was, and I could not for the life of me even begin to imagine seeing any semblance of significant success in the future. I strode to Josh’s office to tell him this, and I found him staring into space in front of him, an accumulation of sleep and crust layering his twitching eyelids. When I arrived there, he didn’t even let me begin, just looked up at me with irritation.

“You jealous it wasn’t you?” He croaked.

“What?” I said, genuinely confused.

“At the party. You could smell that stink eye you were giving Lisa from a mile away.” He said. “Come to bitch about that or something?”

“N-no.” I said, offended. “I’ve come to tell you that I want to…to tell you that I’m quitting.”

He stared blankly for a moment, like a fish.

“Shame.” He said after a while. “I did that to get to you, y’know? Make you jealous? Usually works with birds.”

“What the hell is wrong with you Josh?” I asked, appalled. This version of him was foreign to me.

Ignoring me, he continued with a lacklustre drawl. “Right. So. Quitting? Why on earth would you want to do that? The dead kids only just become too much for you because god said it’s wrong? I don’t find that to be too much of a deal-breaker personally.” He paused for a moment, then continued with subdued fury. “You want to leave, do you? You think you can? You think you’ll ever be able to leave any of this behind? You want to take what you give us away, huh? No. No, alright, no, damn it. Stop me if you’ve heard this one before but the show-”

“Shut up! Please!” I cried at him.

He sank back, his emotions going from 100 to 0 in a second, tracking his journey from standing up with his fists clenched, to flopped back down on his chair, hopeless. “Go then. Go.” He said listlessly. “But just know for the rest of your life, it’ll be ‘we’.”

“What the hell are you talking about?” I sighed, tears in my eyes.

He smiled then, with a certain glint in his eye that I almost recognised as the old him. “You know, Kate. You know. It’ll always be us. We’re an entity, now, I suppose. All a part of one body. A body I’m beginning to think doesn’t know what to do with itself.”

Then, Abigail Meline came in. She was crying, and she apparently needed to speak to Josh. He sat bolt upright when she came in, suddenly attentive. He hadn’t degraded to the point of showing it to the townsfolk just yet. I felt compelled, again, to comfort her, and tried to coax her into stringing together a coherent sentence, however the closest I could get was “oh god I’m a horrible person.”

After a while, it seemed like this wasn’t working, so I tried something different.

“Alright, honey, why don’t you start from the beginning?” I said. Josh nodded to her, encouraging.

Shaky, Abigail nodded. She started telling us, her story occasionally broken by snorts and sniffles, about how about a week ago Dennis started asking uncomfortable questions to her. “Why don’t I have any brothers or sisters?” He’d ask. She initially shooed him away, though later on, he’d started saying other things.

“Why do you hate me, mommy? Why don’t you like children?” She described how she’d got a lump so large in her throat when he asked that she almost couldn’t answer. Abigail had always seen children as irritating, and a disadvantage to life, as well as thinking it inhumane to bring other people into this world. While she was telling us this part, me and Josh shared a look of guilt. She seemed to have lived under our regime so long that she’d forgotten it was us who made her have a child originally. She told us, in an almost confession-like manner, how she really had come to love Dennis, despite how strange a child he was. This only made her seem more distressed.

However, then she started having dreams that she described as similar to the one I had of the dead children, only in her’s, she was throwing the bodies into the pit herself. She said she didn’t sleep for several days, just so she didn’t have to see that. After not sleeping for at least three days, she began to think that it was somehow Dennis’ fault. Whatever we were doing to him was giving him the power to affect her dreams. Later that day, she said that she thought she heard a bird talking to her.

“Killer.” It said in a cold and arrogant voice, a woman’s voice, she said.

She started breaking down properly at this point. “I was only 15” was all she could say. My heart sank for her. The spirit was fiercely vengeful of children to a degree we had not anticipated.

Then, Dennis came into her room one night. He told her that he’d been speaking with his sister. Dennis told Abigail about his nameless, jealous sister, who’d been calling him names, and putting his stuff in the wrong places. “She’s annoyed mom. She’s annoyed you gave me a chance and she didn’t get one.” Dennis was crying, shouting at his mother. “Why did you kill her mom?”

Abigail had grabbed a belt on the bed beside her and struck Dennis three times, screaming in rage.

“Oh god, I’m sorry. Please, please stop, I don’t deserve any help. I’m a horrible person.” Was all she said after that.

Josh was staring into space again when she finished. He’d then taken her to see Dennis in his cell, watching sadly from the doorway as she hugged him tightly.

Night fell like a corpse shroud, and we heard the storm approaching from beyond our walls. We’d sort of accepted it. Maybe if we all just stayed here, it would destroy us too, this old god wiping all evidence of our blasphemy from the earth so our gods would not learn of it. Maybe that was for the best.

We got messages from the townsfolk, who said that they were trying to evacuate, but the roads were all blocked somehow. We didn’t respond to them.

Later that night, Trevor the guard, who patrolled the dark halls past his shift for that night, found Eric in one of our offices, highly classified files spread out around him like comic books on a bedroom floor. He was studying one closely.

“The hell are you doing you little runt?” Said Trevor.

“I’m learning how to write reports. For my research.” Eric said. He had not been surprised by Trevor, judging by how in the surveillance footage he barely moved a muscle.

Trevor had never tolerated anyone he was allowed to bully disobeying him, and it was a hell of a day to break this pattern. “Get off your ass and go back to your cell you little freak.”

Eric put down the file and sighed, then stood up, hands on his head and his eyes closed. “Okay. But I’ll only go if you get me a glass of water.”

“What?”

“Go and get me a glass of water. And walk like a chicken while you’re doing it.”

“The fuck did you just say to-” But it was too late, Trevor was already turning on his heels and bopping his head out in front of him, hands tucked into his armpits with his elbows flapping at his sides. “Cluck cluck.” He said, eyes glazed over, as he disappeared back into the dark corridors.

Eric chuckled to himself as he sat down and began to read the file again. It was a good one, all about this weird living ball the organisation had been given which evolved whenever they did anything to it, so they had to find new ways of opening each time.

He was reading about how they’d put children in there for experiments when he stopped. He could hear someone behind him. He stood up, and turned around to see the glint of something metal in the darkness, alongside the menacing shape of a man approaching him. A familiar man, a man he knew to be great.

Eric had seen Trevor coming, he had seen everything that had happened so far, the man who stood in front of the car, the storm, him and his friends getting taken here, he’d been able to anticipate what would happen next his whole life. But whatever was in the dark, he had not seen yet. And he could not see what would happen next. His voice, usually self-assured and callous, hitched in his throat as he stammered out to the figure. “W-who’s there?”

When Trevor had come to, he had hobbled to and from the water dispenser, carrying a paper cup perfectly balanced in his jutted out mouth. When Trevor came to from hypnosis, he dropped the paper cup on the floor and let it spill. When Trevor came to, he saw Josh Bleeker holding a pistol to Eric’s head.

“Josh?” He asked, utterly bewildered.

Bang.

“The show must go on.” Josh said sadly, shoulders sagging.

Bang.

In his cell at that moment, Louis, who was sitting on the floor savouring a cockroach that had crawled from between the walls, suddenly began to feel something against his forehead, a kind of pressure. It was like the feeling of the oncoming march of sleep, only it slowly became more painful until he was wriggling on the floor, gritting his teeth. Then, the pressure came to a peak, whatever force was trying to get in his head had finally found a nice, soft part. The inside of his head exploded as the pressure ripped through it, coming out the other side and making a large dent in the wall behind him. Louis did not feel pain for long after the force was tickling around his head, but the few seconds before he died were excruciating. Dennis was sleeping when it came for him, the first time he had dreamed in his life, about his sister hugging him, telling him she was sorry, and he felt nothing. The storm outside abruptly resided.

The next day was the most horrible of all, but simultaneously the easiest. All of my burdens had been relieved. All three of our subjects had died, alongside Josh. What was slightly more messy was Bleekerville. Swathes of the identical houses had been splintered and scattered all across the surrounding area by the winds, one struck by lightning and had been transformed from a tame suburban home to what might look like an industrial factory from afar, metallic black and bellowing smoke into the sky. Cars had been thrown up in the air as families attempted to escape, and had been lodged into the branches of trees, or carried into street lights and smashed in half.

Half of the population had died that night, crushed and battered by the detritus swirling around them. Among them, Abigail Meline and her husband, as well as Louis’ parents, and Mrs O’Leary. Mr O’Leary had to be torn from her body, thrashing and beating his fists weakly at the recovery team. He was never told what happened to Eric and died only a few months later in a drunken fight. Those who survived were given all they were promised, and those who did not were buried in the same town graveyard, which until then had been full of the hollow graves of imaginary people. Among the dead there were no children, who had all been miraculously protected from any kind of harm during the storm. All of them, even the ones who had lost their parents, came out of the experience with no substantial sign of mental trauma, and all of their memories of the town completely vanished quickly afterwards.

And that was that really. The whole team made it, in the end, and since this had dismally failed, it was back to the drawing board. That veiny headed freak who suggested this eats lunch alone again, and he barely speaks during team meetings. We got a new director, some slimy old fat man who perpetually wears black-tinted glasses.

Apparently, they’re going to start sending us children again soon.

I did not quit. Josh was right, I couldn’t. I had one foot in already, all I could do now was place the other in.

And so I did, I have continued to work in this department until the present, continuing to help terrorise innocents for no sensible reason. Because at this point, what else can I do?

We will continue, as long as the government pays us, as long as there are childhoods to be ruined and as long as there are mysteries to scratch the surface of then run away from what was seen beneath the scar.

The show must go on.